Blog

Black History Month: Black Women in Catering

Black women have played a remarkable role in the food and hospitality industry as a whole, both prior to the abolition of slavery and specifically following the Civil War. But the common media and entertainment industry has only touched the surface of just how deeply entwined our relationship with food as a nation is with that era. The menus chosen by the black female cooks of that day are a staple of many southern restaurants to this day.

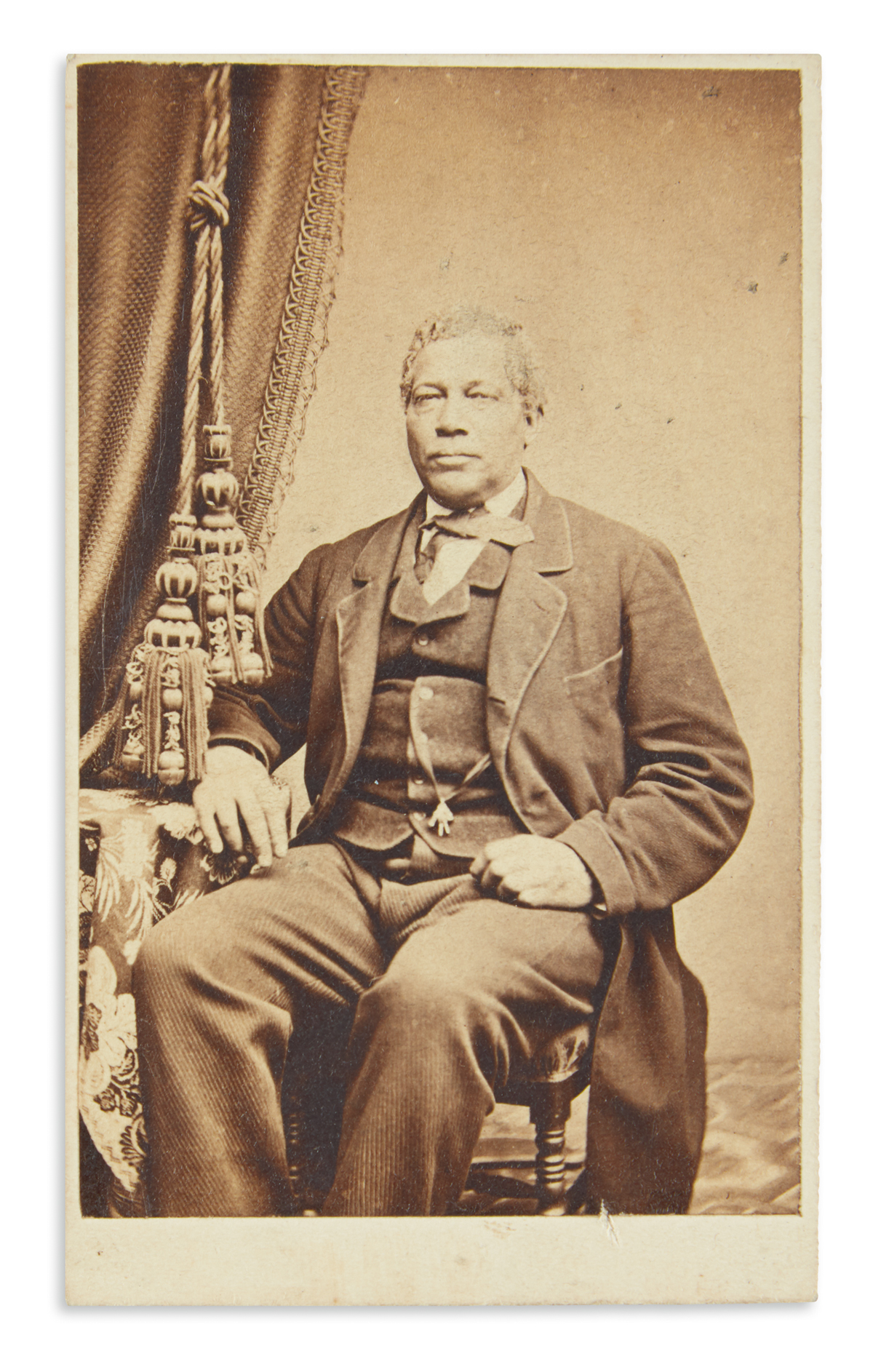

In the second half of the nineteenth century, these women combined their work in domestic vocations with social activism during the Colored Conventions movement. The meetings kept committee reports which show us the cuisine offered at them as well as advertisements for boarding houses that often discussed the food served to guests. It may seem unrelated, but it is believed that these women took the opportunity to express their political views through their choice of menu in many of these settings.

Refreshment rooms at the conventions were known to facilitate further discussions during breaks and as the attendees enjoyed meals prepared by many of these creative and astute ladies, it’s impossible to imagine they did not join in conversations with their customers, undoubtedly playing a role in shaping opinions on many matters. The crafting of menus was a deliberate and painstaking process that these hostesses took upon themselves to communicate messages of affinity. Many of these women along with convention honorees are revered as influencers of the movement, and though they experienced even more obstacles than their male counterparts, they crafted a place for themselves to be heard within the political discourse of the times.

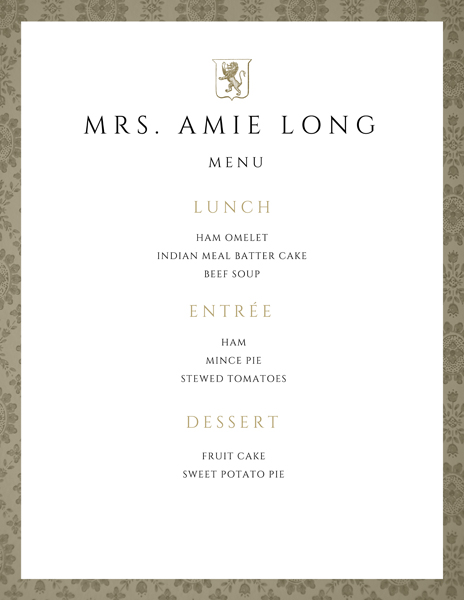

Mrs. Amie Long was one of these women. In her home near one of the convention halls in Delaware County, PA, she served meals during breaks and her meals were known as some of the best to be had, especially in that they were indicative of the mood of the crowds. Though her political presence is perhaps undocumented, she hosted some of the most attended dinners, catering to the attendees with both her vibrant conversation and her beloved culinary abilities. Her mince pies were especially sought after, and her Indian Meal Batter Cake recipe along with several others landed in a popular cookbook of the times by Malinda Russell.

Mrs. Amie Long was one of these women. In her home near one of the convention halls in Delaware County, PA, she served meals during breaks and her meals were known as some of the best to be had, especially in that they were indicative of the mood of the crowds. Though her political presence is perhaps undocumented, she hosted some of the most attended dinners, catering to the attendees with both her vibrant conversation and her beloved culinary abilities. Her mince pies were especially sought after, and her Indian Meal Batter Cake recipe along with several others landed in a popular cookbook of the times by Malinda Russell.

Russell, who was born free in Tennessee in 1820, had planned to immigrate to Liberia in her youth. But in running a pastry shop, found herself to be a keen businesswoman. She fled with her family to Michigan at the start of the Civil War and went to work on writing A Domestic Cookbook and becoming the first Black woman in the United States to be published.

During the turn of the century, the catering movement became more commercial, with Hotel Caterers earning popularity. African-American caterers held onto their prominence in select areas of the country and did so by narrowing their clientele to the highest of society and providing everything needed for private parties including china, silver, and decorations. While the boarding houses and meeting spaces closed, these women didn’t simply drift away. Many of them were beloved members of the community and were held in such esteem that they were supported in their endeavors to open restaurants, bakeries, and cafes, where their political banter was enjoyed well into the 20th century.

In the south, where the discourse was much more hostile, black women were industrious in their drive for success. Kept to kitchens and dining rooms, it was much more difficult for them to rise to prominent society than those in the northeast. But those with will and talent did not allow themselves to be held back. Many black caterers were so sought after as home cooks that they eventually found themselves in the employ of companies who paid them handsomely catering dinners for VIP clients and special events.

A copy of “What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking.” Credit…The Michigan State University Libraries

While there is little documentation of the women who lived these lives, there are a few like Abby Fisher, a former slave who penned a cookbook after moving to California and establishing a well-known catering business there, discussing her life as a private cook turned caterer and shed some light on other successful businesses run by Black women of the day.

Fisher competed in and won several prizes at local fairs in San Francisco in 1880, making quite an impression on the social elite of the city. So much so, they convinced her to publish a book based on her experiences. Illiterate but empowered by beautiful diction, her high society friends wrote the book for her, as noted in the “Preface and Apology” of What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking. Listed independently from her husband in a state census in 1882 as a pickle manufacturer, Fisher operated successfully into the 1890s.

Many of these women would have gone forgotten if it weren’t for the diligence to preserve Black History. Mrs. Fisher’s book was nearly lost to the earthquake and fires of 1906 until Applewood Books was able to reprint it in 1985 when Harvard University purchased a copy that resurfaced at auction. There are undoubtedly many like Fisher who was never taught to read or write, having to rely on others to tell their tales. And it is through culinary heritage that those stories live on.

References:

https://blacksouthernbelle.com/black-southern-caterers-a-history-of-enterprise-and-culinary-good-taste/

https://coloredconventions.org/boardinghouses/what-did-they-eat-mrs-amie-longs-menu/

https://restaurant-ingthroughhistory.com/tag/black-caterers/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abby_Fisher